Dr Jenni Hyde, Lancaster University

I came to history through music. As a child, I loved folk songs, both traditional and contemporary, about the past. I still do. So you can imagine my delight when I found a set of ballads, or popular songs, on the downfall of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s right-hand man and architect of the English Reformation.

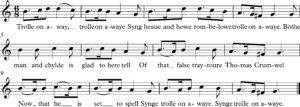

Someone wrote a song celebrating the fact that Cromwell was set to spill his blood, dying for treason in 1540. It claimed that Cromwell had taken advantage of his position during the dissolution of the monasteries in order to steal the expensive goods which were confiscated from the religious orders. It claimed that the king had taken pity on the lowly Cromwell, promoting him to a role that he was ill-fitted as a commoner to occupy. It claimed, moreover, that Cromwell was a ‘false heretic’ – a Protestant who would spend his afterlife in eternal damnation.

The three main facts here are probably correct, even if suggesting that Henry VIII promoted Cromwell to high office out of pity is a wilful misinterpretation of the king’s motivations. Cromwell’s elevation to Earl of Essex only weeks before his execution was, we can assume, entirely about his ability to get things done and to appear to do them for his master the king.

But soon, one of the disgraced minister’s supporters wrote another song defending his former patron. The balladeer had to acknowledge that Cromwell was a traitor according to law, but he made the incredible assertion that the king had already forgiven him. What is more, despite the fact that Cromwell was officially accused of holding unorthodox beliefs, the singer denied that Cromwell was a heretic. And by way of defence, the balladeer launched a counter-attack, accusing Cromwell’s detractors of ‘papacy’ – by now it was treasonable to be loyal to the Pope, as he was a foreigner.

From this point, the musical debate took off. A whole series of ballads and a pamphlet were published that debated what it meant, in these early days of the Reformation, to be a Protestant heretic, a good English Catholic, or a Roman Catholic traitor. And, despite the fact that they quickly descend into entertaining mud-slinging, what they show is that there was an awful lot of confusion about Henry’s religious policy and what it meant to be loyal to the king in increasingly uncertain times.

There was only one problem: they had no tunes. As a musician, and a former music teacher (even though my degrees are all in history!), I see music as fundamental to understanding the role of ballads in any period. Particularly so at a time when there was only limited literacy and access to news and information was reliant, for the most part, on face to face contact.

In the middle of the sixteenth century, there were no regular newspapers, so songs presented an exciting, entertaining and memorable way of passing on news and information, and they took debate about matters of politics into the streets. We know that, on occasion, balladeers were asked about songs they had sung in the past, when political times had changed and made the views they had expressed suspect. We even know that at times, ballad melodies could take on particular associations which added meaning to the words, making it important to know what tunes were used.

But even at a very basic level, I believe that music matters. Melodies are inherently memorable, which means that they helped people to remember the words to the songs. If you wanted to get a message out, either to promote a cause or just to make money, then a ballad was a good way of doing it. And if you wanted your song to sell, in either the material or metaphorical sense of the word, then you needed to make the words, music and opinions attractive to as many people as possible.

For me, then, ballads offer a way in to the minds of ordinary people in the sixteenth century. Even if they were not written by ordinary men and women (and certainly, those Cromwell ballads weren’t!), they were written to appeal to them, so they give us an insight into the issues that balladeers thought were important to people. Yes, God and death loom large, but the number of songs about topical events is noticeable. And while the detail might be lacking in some areas, we mustn’t forget the social context that surrounded these songs. They weren’t learned from books or even, as a rule, from printed broadsides. Instead, they were passed on face to face, from one person to another. As such, they promoted the discussion of current affairs by people who had no official role in politics. Nevertheless, there was no such thing as free speech, and at times it was necessary to hide the exact meaning of the words behind metaphor and allusion. If the audience didn’t entirely understand, they could ask the singer what he meant, but if the singer didn’t trust them he wouldn’t have to explain. This could make it difficult to prove concrete meanings to potentially seditious songs which challenged the regime’s policy, for example in the Cromwell ballads. I’m not saying this sort of hidden ‘knowing’ subtext happened all the time, but that’s one reason why it can be particularly effective when it does appear.

That’s why I think ballads are such a rich vein for understanding the Tudor period: they were accessible, entertaining and created a social space for engaging with a changing world.

Singing the News: Ballads in Mid-Tudor England

is published by Routledge

About the Author: Dr Jenni Hyde is Associate Vice-President of the Historical Association and works in the history department at Lancaster University. She is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. She is a former music teacher, a classically-trained soprano and a keen folk singer.

Where can I hear these ballads? This will be a fantastic teaching resource

Hello Lou

There are recordings of the songs featured in the book on my website https://earlymodernballads.wordpress.com/singing-the-news-ballads-in-mid-tudor-england/

For other recordings of early modern ballads, you could visit the English Broadside Ballad Archive (EBBA) http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/

I hope that helps!

Jenni