Dr Beatriz Pichel, de Montfort University, Leicester

Every year, I give an introductory lecture and seminar on photographic history to first-year students. The aim of this session is to give a flavour of the kind of questions we ask in my second-year module “Visualising the Modern World”, and to spring curiosity about photography among the students. I always start with the same exercise. I project Figure 1 on the wall, and ask them basic questions about what they see, what they think this is and when it was taken. Responses vary, but usually, students see a family (mother with two children) in a garden, and date the picture from the nineteenth century.

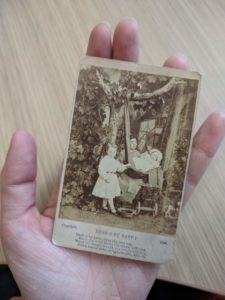

Then, I hand them Figure 2. This is a carte de visite that I bought at a flea market in Bristol some years ago. I let them familiarise themselves with the object (its size, its material form, the inscriptions on the cardboard) and I repeat the same set of questions. What do you see? What do you think it is? When was it made? The responses are now very different from the previous ones. Students recognise the lullaby at the bottom of the image, and notice the ‘copyright’ sign and date (1856), so they conclude that this is not a family photograph, but a studio picture intended to be sold. The small size (smaller than an iphone) make them think that it was supposed to be carried around and that it was easily collectible. The cardboard and the quality of the image suggest that it was cheap. These are the typical characteristics of mid-nineteenth-century cartes de visite. But the students do not need any previous knowledge about cartes de visite, as all these ideas have come from the analysis of the photographic object. From here on, we can discuss broader issues related to the development of the photographic industry, the class system, etc.

I find using photographic materials in my teaching very useful for several reasons. First of all, students get excited with these kinds of objects. Not many of them have touched, with their own hands, photographs and cameras dating from the mid-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The vintage revival in the digital age makes handling old objects a strange but stimulating experience. It is also a lot of fun.

Secondly, spending time with these objects helps students to understand photography as both a visual and a material practice. This is, for me, the most important point. Bringing objects to the classroom (cameras, glass plates, albums, prints, etc.) demonstrates that photographs are not images in a vacuum. As in the example above, interrogating the image alone can only provide so much information. Furthermore, we never experience images floating out of context. We look at photographs that are printed on billboards or magazines, on screens, or in an album, etc. These contexts of reception will shape the understanding of the image. Similarly, photographic cameras shape the relationship between the photographer and the photographed person/object. The history of how photographic technologies have enabled or hindered these relationships allows us to analyse different layers of photographic practices.

This exercise is particularly important to History students, because it leads us to rethink the kind of questions we are going to ask. Photographs have often been considered as ‘windows’ to the past. As a consequence, students tend to ask whether a particular photograph is an accurate representation of reality or not. But this is a limited approach to photography. If we are to fully consider photographic materials as historical sources, we need to interrogate images and objects, as well as the contexts of production, reception and circulation. In other words, we need to look at photographic practices. Having a variety of photographic materials in class, instead of only images projected on the wall, help students to grapple with these ideas.

More importantly, thanks to these objects, photographs stop being passive illustrations to become historical agents. Photographs do not simply corroborate what the text says, but become historical evidence of social, cultural and political practices. This means that we can do any type of history through photographic sources. Coming back to my second example, we can examine the history of the cartes de visite, the kind of images they usually had, or the studio photographers that produced them. But we can also discuss social aspirations and the creation of networks through cartes de visite. My aim in my teaching (and my research) is to demonstrate that photographic sources are very good sources for the social and cultural history of modernity, and I believe that working with materials provides an excellent gateway.

Read about Teaching with Objects

About the Author: Dr Beatriz Pichel is Research Fellow at the Photographic History Research Centre, de Montfort University, Leicester. She specializes in photographic history, the history of medicine, the cultural history of war and the history of emotions, and is currently writing a monograph on photography and combatants’ experiences in France during the First World War. Her new project explores photography in the making of medical specialisms in 19th century France.