Dr Henry Irving, Leeds Beckett University

One of the most important things I learned during my undergraduate degree was that academics read differently. Critical analysis, the lecturers’ said, was as important as comprehension. I still remember feeling shocked when one explained that they would begin marking an essay by looking at the bibliography. “But, what about the content?” I gasped.

What I didn’t know then is that I would end up saying similar things to students of my own. And it turned out that this way of reading is not just for essays. Like it or not, I now spend as much time looking through abstracts, introductions and bibliographies as I do with narrative chapters. Recently, though, I realised that I was still overlooking one part of most texts: the acknowledgements.

Historians are – on the whole – less explicit about their methods than academics working in other disciplines. We are also notoriously shy about the motivations for – and personal experience of – our research. Acknowledgements, however coded, provide a glimpse into these mysterious areas.

I hope you’ll forgive me for using a personal example, but I want to illustrate this point by explaining how and why I came to acknowledge certain individuals and organisations in my latest article. The piece in question – ‘We want everybody’s salvage!’: recycling, voluntarism, and the people’s war’ – is due to be published by Cultural and Social History later this year and is currently available online.

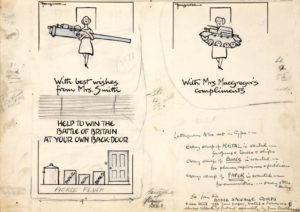

The article shows how the rhetoric of the ‘people’s war’ was applied to – and shaped by – efforts to increase recycling (then known as ‘salvage’) during the Second World War. It is drawn from a wider body of research on this topic and should be suitable for both advanced research and introductory teaching. I do hope that you’ll read it, but let’s stay focused on the acknowledgements for now:

I am incredbly [sic] grateful to the Royal Voluntary Service Archive and Heritage Collection, all of the interviewees who contributed to the project, and the Voluntary Action History Society for their comments on an earlier version of this paper. I would also like to thank the editorial team at Cultural and Social History and my two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on this article.

What’s the first thing you notice? That’s right, a spelling mistake, which perhaps just goes to prove that these parts of our work are given less attention than they should. No, it was not deliberate.

In terms of content, each clause contains a lot of hidden meaning. The first sentence refers to both the source-base and the writing process. The second sentence concerns the publication process and is a classic of the genre. There is apparently an ‘etiquette of thanking’ and I would not be surprised if another author in the same volume says exactly the same thing. They just won’t have included a spelling mistake.

So what does it all mean? The article’s introduction provides another hint. I refer there to ‘material housed by the Royal Voluntary Service Archive and Heritage Collection’ and ‘a handful of more recent interviews undertaken by the author’. I end by claiming that:

In combination, these sources provide greater understanding of the everyday actions upon which wartime recycling depended and help to reveal this strangely overlooked part of life on the home front.

This is the real reason why I started to research this subject. I find salvage fascinating because it involved mass participation in an activity that brought the war effort into a domestic setting. Recycling was presented as an opportunity for action, more akin to ‘Digging for Victory’ than ‘Making do’ with rationing. And yet – despite the vast majority of British civilians taking part – it has been far less well remembered than other parts of life on the ‘home front’.

My early research focused on publicity campaigns (see ‘Paper Salvage in Britain during the Second World War’), but I was frustrated by how difficult it was to piece together the social and cultural dimensions of the subject. It was not until a fortuitous visit to the Royal Voluntary Services Archive and Heritage Collection that this began to fit into place. Their archive – which has since opened to researchers – provided insight into the everyday experience of the women who were partly responsible for the scheme.

The RVS archive also confirmed the important role that children played in the collection of waste materials. This gave me the spur I needed to undertake a handful of oral history interviews with people who grew up during the war. I had hoped to expand this part of my research, but an unsuccessful funding application left me feeling even more grateful to those who responded to a pilot project carried out in Hull. As an aside, I am still keen to talk to anyone who has childhood memories of putting out the salvage, so do get in touch.

The final part of the acknowledgement refers to the writing and publication process. For want of a better word, it acknowledges that this article was the result of a long process, which has shaped its final form. I refer directly to a paper for the Voluntary Action History Society that was given on 20 November 2017. Most of the research had been carried out during the previous year, but the invitation from VAHS led me to produce a first draft, which was revised following a lively discussion with the audience. The article would have been very different had other circumstances transpired.

Of course, this was not the end of the process. My revised draft was submitted to Cultural and Social History at the end of March 2018 and was sent to two anonymous reviewers. In July, I was told that the reviewers had been ‘very positive about the piece’, but had identified a number of points that could be clarified. Their comments helped me to strengthen the argument and a revised version of the article was accepted at the end of August 2018. At that point, the editors took back over, answering my many questions about image licensing. Finally, in March 2019, the article was ready to be published online and I hurriedly wrote the acknowledgements while answering emails about undergraduate essays.

This is the first time I’ve shared the work that goes into an article in this way. At this stage, I can’t decide whether it is a useful reflection, or a horrible self-indulgence. My only certainty is that we should always acknowledge the acknowledgments.

Read more in the Cultural & Social History article

SHS members can access the journal via this website here.

Read more blog posts by CASH authors here.

About the author: Henry Irving is a senior lecturer in public history at Leeds Beckett University and is Communications Officer for the Social History Society. His spelling is notoriously bad.