Dr Rachel Duffett, University of Essex

Your starter for ten – what do the following constructions have in common?

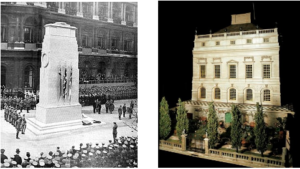

Answer: Sir Edwin Lutyens

Lutyens is the national architect of the commemorative legacies of the First World War; his aesthetic of remembrance dominates the visual culture of the conflict’s losses from Whitehall to Thiepval. Yet, in amongst the designs for monuments, stones and cemeteries, Lutyens found time to involve himself in a project of a very different nature – the design, construction and furnishing of a dolls’ house presented by a grateful nation to Queen Mary. The conduit for this wave of gratitude was in fact another member of the royal family, Princess Marie Louise, rather than a band of loyal citizens, but few could doubt the Queen’s stalwart contribution – the charities established and the countless hospitals and factories visited. Queen Mary was a great collector, indeed her fascination with the accumulation and display of objects rather exceeded her interest in human relationships, including those with her own children. Her son David regarded her as ‘a cold woman’. She was also an admirer of all things miniature from Fabergé’s eggs to the less valuable ‘tiny craft’ that she collected for her glass cabinets at Sandringham.

The dolls’ house seemed both an appropriate gift to the nation’s matriarch and an opportunity to showcase all that was best about British craftsmanship, culture and design. Lutyens was tempted into the scheme through his friendship with Princess Marie Louise and it appealed to his own fun-loving nature. He had designed the original stage sets for Peter Pan and the 1924, Everybody’s Book of the Queen’s Dolls’ House, stated that a sense of play was central to this new scheme and Lutyens had just the personality to lead such an enterprise. It must have presented light relief from the sober tasks of, for example, planning a suitable setting for the eleven thousand dead at Etaples or the sixty thousand missing at St Quentin, work with which he was simultaneously engaged.

Lutyens put a huge amount of time and energy into his miniature project, designing the structure and various pieces of furniture himself. The remainder of the house was decorated and furnished through donations from individuals and companies who had received letters inviting a contribution from the architect and his committee. The house was a miracle of miniature technology, from the pair of Purdy shotguns that actually broke even if they didn’t fire, to the electric lift and working plumbing.

It was also packed with beautiful and very tiny works of art and literature that represented a major shift from their creators’ wartime output. C.R.W. Nevinson’s “Paths of Glory” had been banned in 1918 because of its shockingly unpatriotic content of faceless British corpses lying in the trench mud, but his contribution to the dolls’ house was a pretty watercolour of a mountain town. In 1917, Sir William Orpen had painted “Two Dead Germans in a Trench”, a vivid contrast to his formal portraits of King George and Queen Mary that were hung in the saloon. Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon handwrote miniature books for the extensive – around two hundred in total – dolls’ library and John Buchan produced Battle of the Somme, condensing the whole horror of the blood-soaked campaign into a leather-bound volume the size of a postage stamp.

The legacies of the war are numerous and evident throughout the house; from Jagger’s bust of Haig in the upper hall to the photograph of an unknown Tommy by a maid’s bed, but they are all safely contained within its walls. The dolls’ house is a time capsule, preserving a way of life that many felt had already been lost in the war, but the painstaking reconstruction incorporated the conflict’s raw reality into a domestic setting in which it could be contained. The wartime protests of men such as Nevinson and Orpen were pushed back into the past and their miniature contributions were evidence of a return to the order and stability of peacetime.

Read more in the Cultural & Social History article

SHS members can access the journal via this website here.

About the author: Rachel Duffett is a social and cultural historian of British society and its experience of the First World War, in particular the social and emotional role of food in military life, see The Stomach for Fighting (MUP, 2012). She is currently researching the legacies of the conflict, including its impact on the leisure interests of adults and children in the 1920s.

The images of the dolls’ house and its contents are reproduced with the kind permission of the Royal Collection Trust.